Collected Memory

FAMILIES AND OTHER PEOPLE

By Barbara Pollack

Author and critic The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Artnews and Art in America.

Danish artist Mille Kalsmose views the world from a very personal perspective, yet her works appeal universally, cutting through cultural boundaries. She has examined what it means to have an identity, what creates this identity and what emotional scars imprint on the self in ways that cannot easily be erased. Her conception of identity is not rooted in nationality or cultural background, but in something almost pre- Freudian, connected to familial ties and personal history that nevertheless transcends blood relationships.

Kalsmose is fundamentally a conceptual artist who has incorporated photography, video, sculpture and technology into her installations. Yet her works are never overly intellectual nor do they alienate viewers with theoretical concerns. Instead, there is an emotional heart to her works that are certain to move viewers even to the point of tears. For her 2012 project, All My Suicides: The Quest for a New Identity, this artist legally changed her name five times over the course of ten years, erasing any connection to her birth name and natural parents. For her later exhibition, Searching for a Mother, she encapsulates her search for a woman to replace her birth mother, whom she lost first to divorce at the age of seven, and years later to suicide, a trauma which has cast a shadow over all of her artistic endeavors. This is an artist who does not take identity for granted nor does she accept that family is an incontrovertible given that one must accept.

Family is obviously the fundamental unit of society. It is also the fundamental experience for most individuals in which they first experience the construction of identity. Yet we have all witnessed the destruction of this bedrock of identity through divorce and personal circumstance, through upheavals and reformation brought on by the severe changes in society at the beginning of the 21st century. Mille Kalsmose does not take the family for granted, having experienced its fragility from a very young age. Instead, she sees it as one factor impacting the formation of identity, offering the possibility that her “I” can be recreated and reinvented as she matures.

In her latest two series, Tribe and Mnemonic Archives, Kalsmose veers away from autobiography to broader social circumstances. In order to make this change, she has shifted her attention away from conceptual installations to more concrete sculptural objects. Nonetheless, her works continue to resonate with meaning, metaphors for social configurations and hierarchical values. It is as if her artworks themselves have changed their identities, becoming full-fledged sculptures, independent of an autobiographical backstory.

Tribe is a series of configurations between connected sculptural figures that can symbolize relationships within a family. For this series, Kalsmose works with iron, wood, silk and pigskin to fashion forms that can be read as “mother”, “father”, “brother”, “sister” and all other members of an extended family. These figures are related, as communicated by the strong similarities between each abstract form. They are also connected to each other by a metal base from which they stand. Yet, these sturdy works also communicate fragility and mortality, as the leather is stretched into the iron frames, fastened in place by rivets, like skin and muscles coursing across a skeleton.

In her own words, Kalsmose describes the Tribe series, as follows:

“Tribe came out of my lack of family and my wish to have an intimate family…

I mimed a family made out of iron that couldn’t move away from me.”

In this way, the works convey an intimacy missing from her own life, yet they do not specifically answer overriding questions about the meaning of a family. Instead, this artist leaves her inquiry to be open-ended by allowing each figure to remain anonymous and unspecific. We are allowed to read into these configurations, to imagine a conversation between each form. The works therefore become a kind of test or mirror, interrogating our ideas about familial relationships and reflecting back on our own personal experiences of home life.

By leaving each “face” generalized and non-specific, these works are also amazingly universal, applying to a wide variety of cultures, both East and west. It is impossible to read these works as “Danish” or “western.” That can just as easily be “Chinese” or “Asian.” At a time when so much of the world insists on cultural differences, Kalsmose has invented a vocabulary that truly cuts across boundaries.

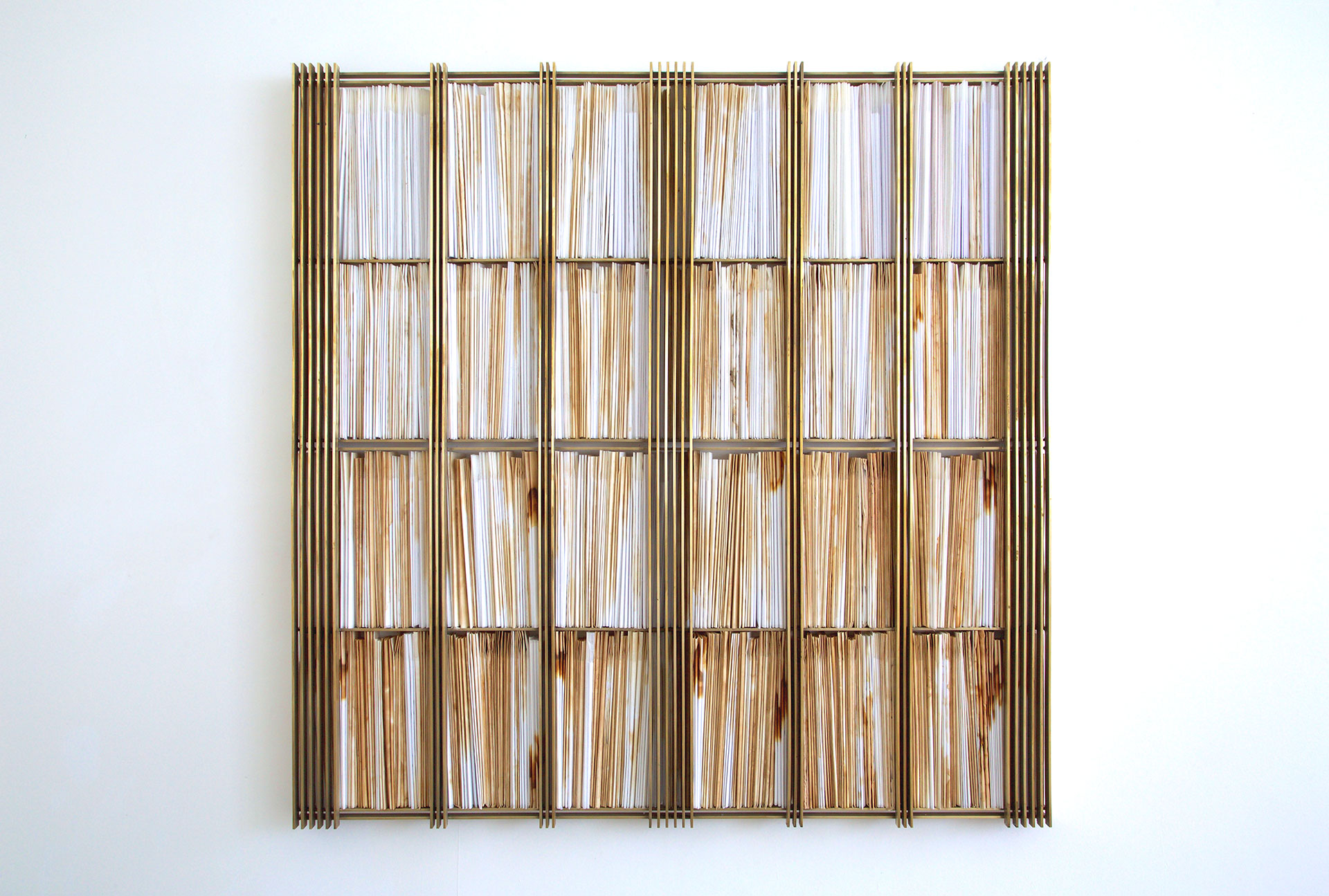

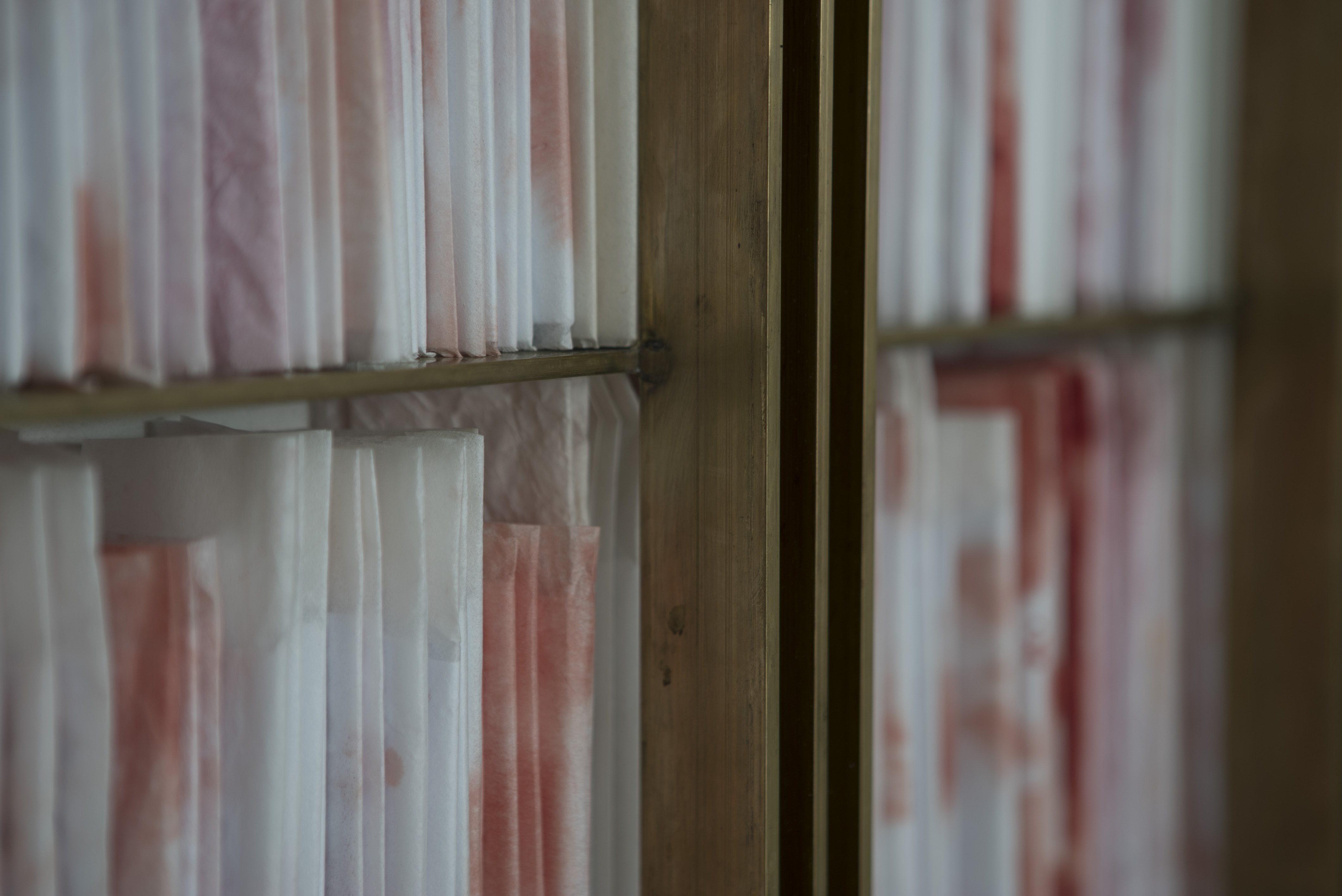

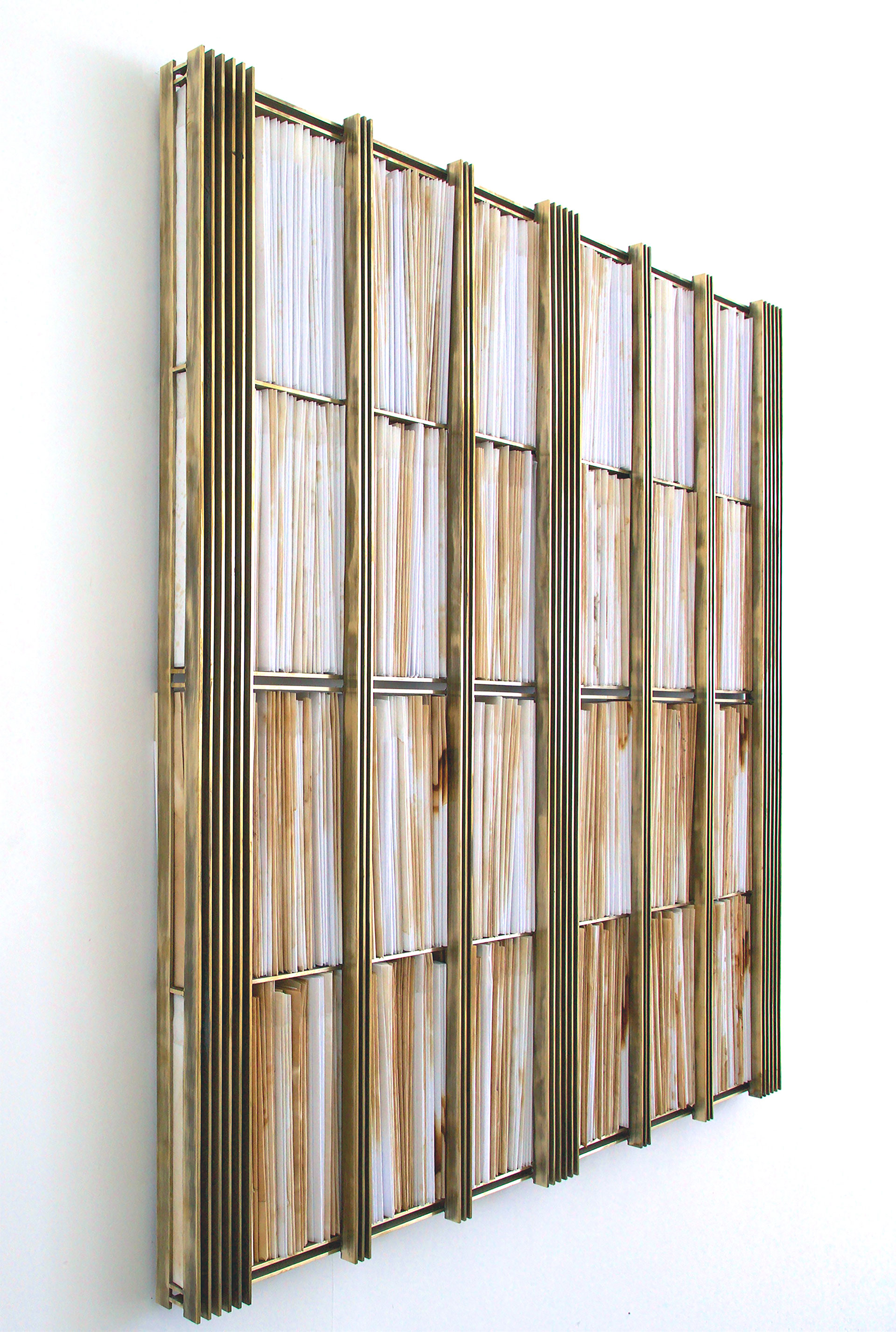

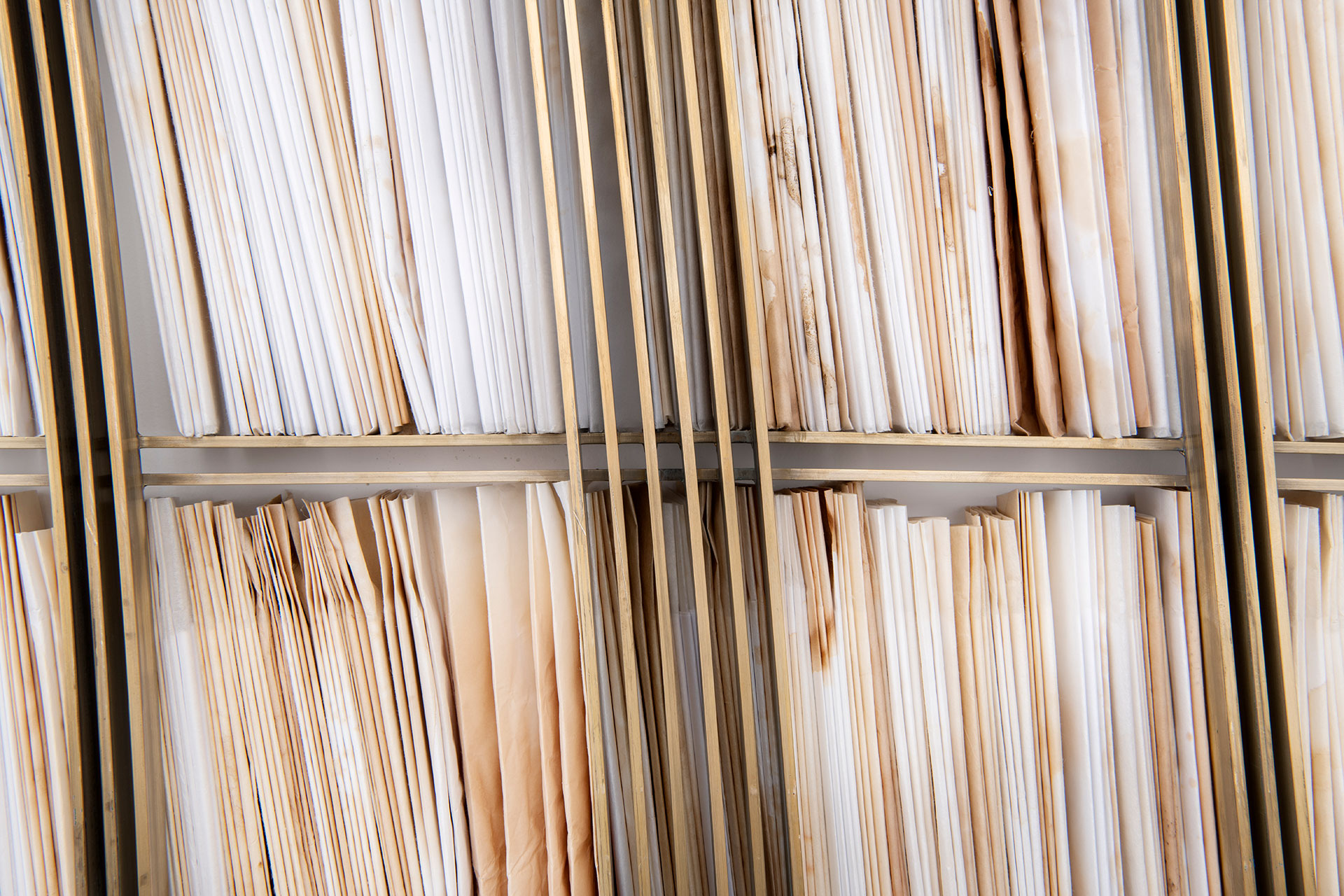

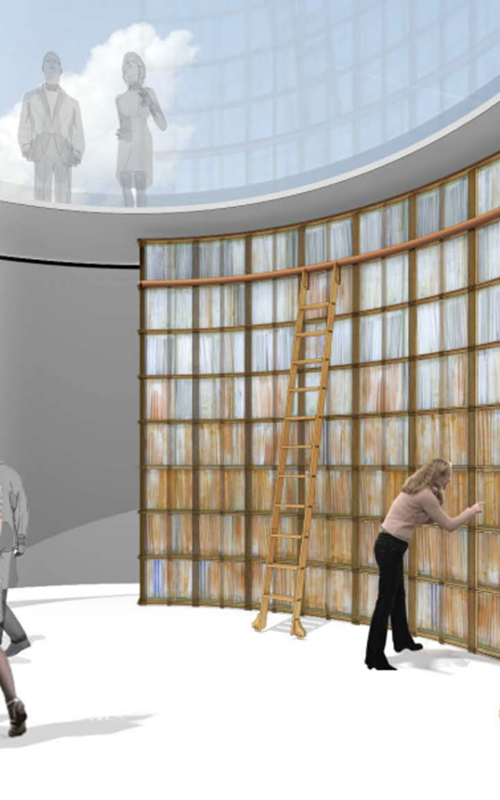

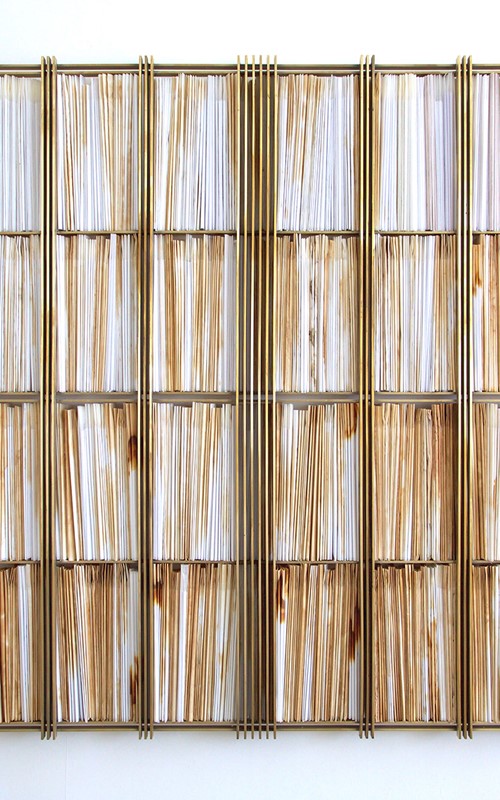

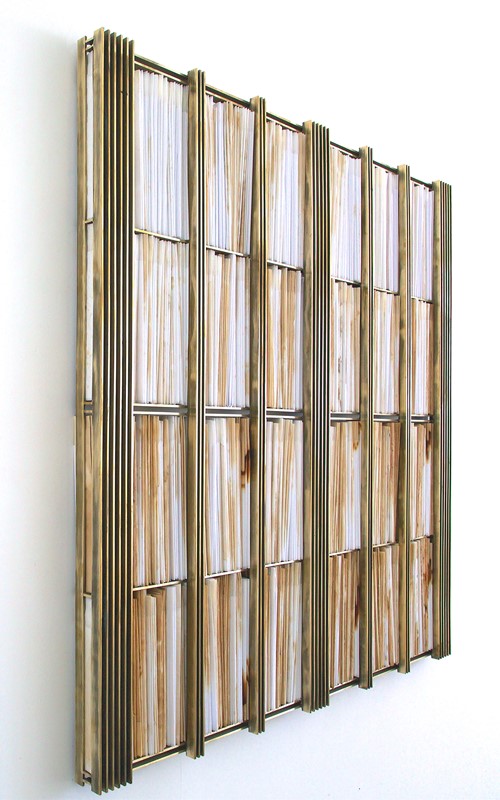

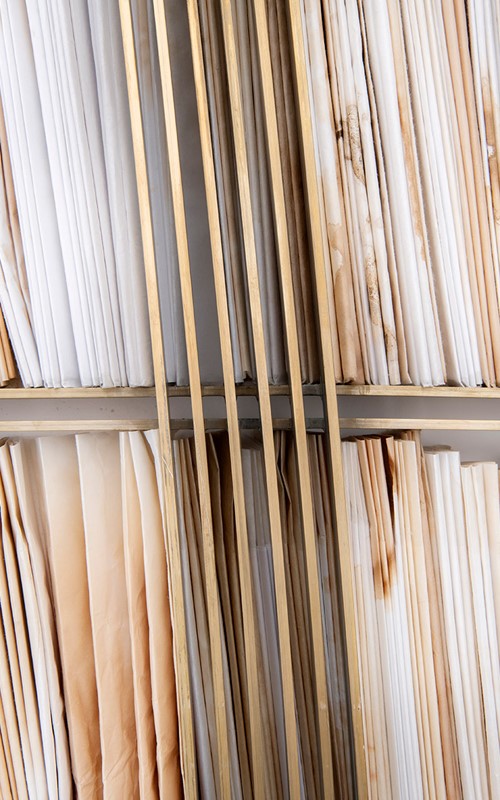

The influence of Asian materials is most pronounced in her latest series, titled Mnemonic Archives. For this series, Kalsmose had brass frames fashioned for her and then she folded hundreds of sheets of Chinese rice paper. The frames stand 2 meters tall and hang on the wall, like a bookcase in a vast library. The paper is stained, in one instance with black tea and in another with cherry juice, which easily creates an association with blood. Carefully inserted in place, this overstuffed archive evokes thousands of birth certificates and marriage licenses, death notices and wills, the reams of paper that accompany life in contemporary society.

For Kalsmose, these works are representative of hierarchies and social conventions that dominate our lives. The associations in these works transcend family relationships and extend to an evaluation of a broader society, in which we all operate within frameworks not necessarily of our own making. There is also a contrast between materials, the hard surfaces of the brass frames and the pliant folds of the rice paper, which mimics the relationship between masculine and feminine qualities in society. In this way, the frames function much as the legal structure, obdurate and difficult to alter, while the folded paper represents the personal lives of citizens, struggling to maintain their individuality in the face of societal pressures to conform.

Memory is also a key factor in this series, delicate memories that cling to our lives even as we try to forget them. In one way, the brass frames can be viewed as a human brain, the mind of one individual, and the sheets of paper are all the memories contained within that make up an individual’s identity. So, these works can be read as either applying to a greater society, governing the lives of many individuals, or as the experience of just one, lone, being, populated by the many experiences that has made up their life.

This ability to read these works on many different levels is a sign of Kalsmose’s talent as an artist. For example, she had no idea that she would be traveling to China at the time she made Tribe. Yet this is a series that can definitely resonate with Chinese viewers who are particularly attune to the importance of family. Similar to Zhang Xiaogang’s portraits of families, Bloodlines, Kalsmose’s sculptures encapsulate familial relationships in ways that are both universal and specific. We can easily see the faces, that the artist leaves blank, as if we are flipping through a family album. Also, the works in the Mnemonic Archives series resonate particularly well in Asia where the use of rice paper is fundamental to the history of art. These works particularly remind me of the Library Room at the caves of Dunhuang where explorers discovered a grotto filled with Buddhist scrolls more than a century ago. Just as those westerners were amazed to find a treasure trove of information packed into an anonymous cave situated in the middle of the desert, we viewers approach Kalsmose’s library in amazement at the feat it took to daub each sheet with colors, to fold and insert each one in its frame. It is an example of an artist’s touch bringing us closer to an intimate experience, now somewhat a rarity in contemporary art.

Combining autobiography with neuroscience, personal experiences with social inquiry, Mille Kalsmose creates artworks that resonate on many levels. She has worked with a wide range of materials, but with her latest works, she reaches a new peak of creativity. These works appear as individual sculptures, independent forms that can be appreciated for purely aesthetic reasons. But each one tells a story about family and society, about the creation of identity within a social framework. These are tales that can be appreciated by audiences from a vast variety of cultural backgrounds. Just as many contemporary Chinese artists have managed to make works that have a global appeal, yet retain the specifics of Chinese cultural identity, Kalsmose has achieved a perfect balance in her work between the universal and the individual. It is impossible to view her works without discovering an element of identification. This makes the experience inescapably emotional and personal, defying cultural boundaries. That is quite an achievement for an artist and for this alone, her artworks deserve widespread appreciation.

For inquiry contact Martin Asbæk Gallery: liselotte@martinasbaek.com